All's well that ends well? Many observers are glad that the endless tug-of-war over the UK's departure is finally a thing of the past. Is the "Brexit drama" now really history?

Christian Kastrop: On the contrary. In some respects, it's only just beginning. Initially, however, nothing will change for the EU and UK as of January 31. We'll be in a transition phase: students and tourists can continue to fly to Cambridge and London without difficulty. Goods will be conveyed between Calais and Dover without customs duties being imposed.

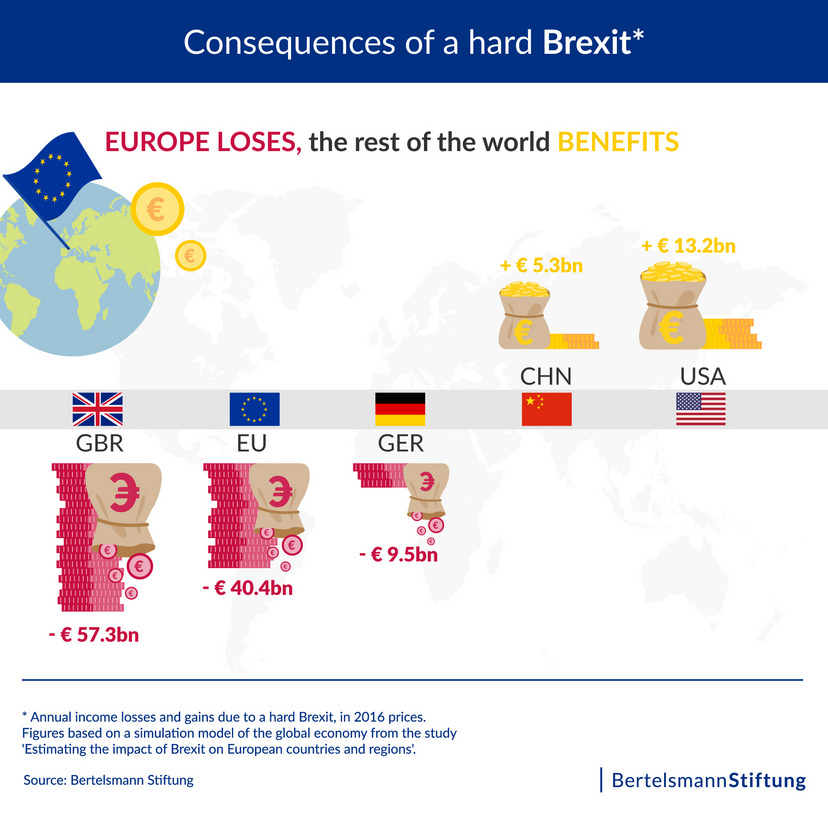

But London and Brussels really need to have the next deadlines written in their calendars in red: In order to avoid a "hard" Brexit, the British government wants to negotiate a new free trade agreement by December 31, 2020. If the talks require more time, then the UK has to request an extension by July 1, 2020. Yet Boris Johnson has already made it clear that he wants to avoid that scenario no matter what. Which means the threat of Brexit happening without an agreement or clear ground rules for the business community is anything but over.

What's more, the "divorce" has taken roughly three years, so why should the new relationship's status be resolved in just a few months? As the new president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, recently said very clearly, a fair deal must be struck, and the two sides' positions – including their views on Ireland – are still far apart. The coming negotiations will therefore be crucial for the shape our relationship with the UK ultimately takes.