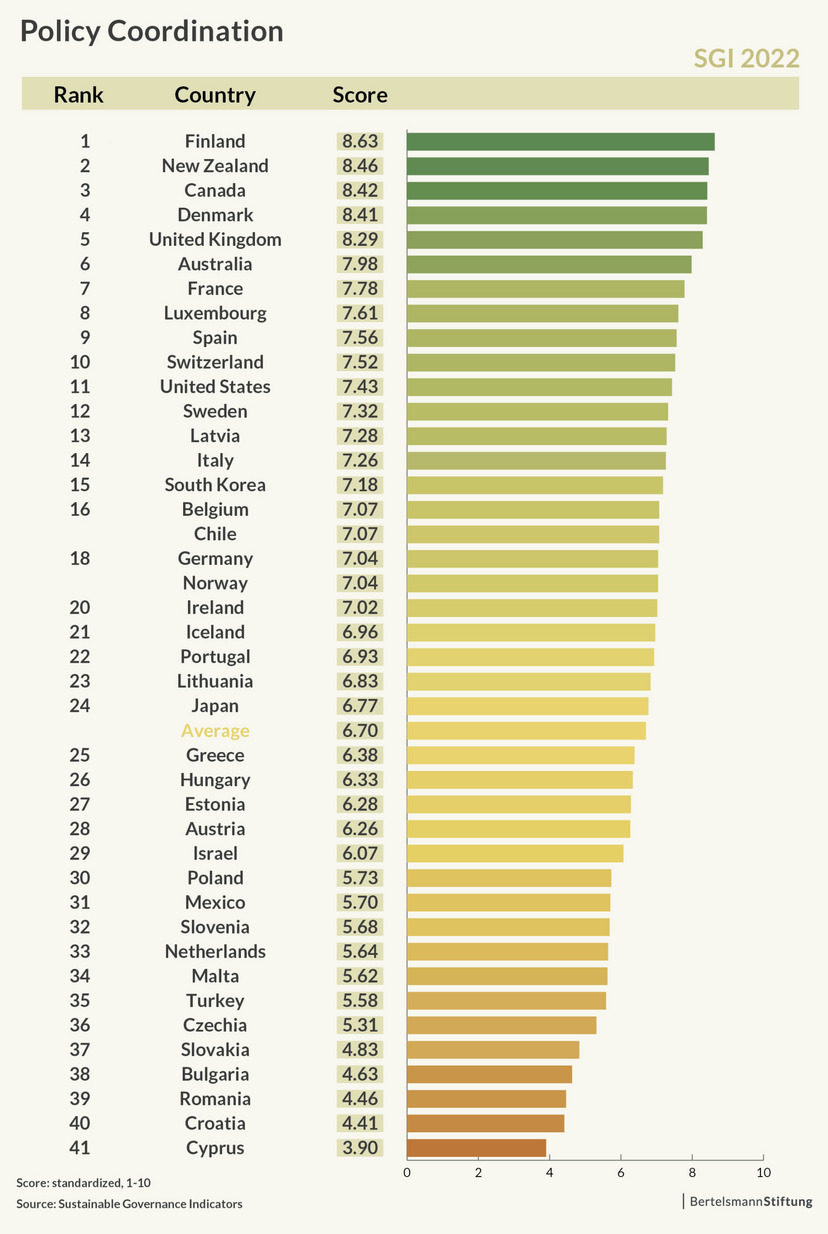

The coronavirus pandemic, the climate catastrophe and the energy crisis have brought the issue of government’s ability to act effectively more squarely into the public eye than it has been for a long time. In many places, confidence in democracies’ ability to solve current problems is declining.

Despite the positive developments seen at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains considerable room for improvement with regard to forward-looking policy coordination, the fashioning of broad-based societal consensus, and the development of strategy in OECD and EU countries. Too few countries have shown they are able to craft solutions capable of meeting future challenges in these areas. "In addition to strengthening democratic institutions and processes, the key is to establish a new way of governing: proactively across silos; humbly and in a way open to the broad inclusion of new knowledge and relevant societal actors; and strategically, with a culture of ongoing learning and trial and error," said Christof Schiller, a Bertelsmann Stiftung governance expert and study coauthor. These are the findings of a study that draws on the most recent edition of the Sustainable Governance Indicators. For more than 10 years, the Bertelsmann Stiftung has used this international monitoring instrument to track the progress made by OECD and EU countries in the quality of forward-looking governance.