Prof. Dr. Aurel Croissant is Professor of Political Science at the Institute of Political Science, Ruprecht-Karls-University, Heidelberg and Regional Coordinator Asia and Oceania for the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI). His main research interests include the comparative analysis of political structures and processes in East- and Southeast Asia, the theoretical and empirical analysis of democracy, civil-military relations, terrorism and political violence.

![[Translate to English:] Proteste in einer asiatischen Stadt](/fileadmin/files/_processed_/5/e/csm_AdobeStock_294882262_KONZERN_ST-DA_Original_93816_01_f7c3512971.jpeg)

© Lewis Tse Pui Lung - stock.adobe.com

The Struggle for Democracy in Asia – Regression, Resilience, Revival

Aurel Croissant

Worldwide, democracy is under pressure. The slow but steady erosion of democracy in many places in the last decade seems to be accelerating since the outbreak of the Corona pandemic. As political leaders seize powers to fight the virus, worries grow if they will give up accrued powers readily once the crisis eventually subsides. In addition, the uneven performance of many democracies in fighting the pandemic rekindles questions about the superiority of political systems and if authoritarian governments do a better job in handling this or other mega challenges than democratic governments. The Asia-Pacific region is of crucial importance for the future of democracy and its global contestation with autocracy in the twenty-first century. The region is not immune to the impositions of authoritarian populism and other illiberal threats to democracy. Yet, it provides both major examples of democratic regression and failure as well as inspiring stories of democratic resilience and revival.

Introduction

Around the world, democracies are in trouble. Data from major democracy barometers indicate that after a long period of democratic growth from 1973 to 2005, an increasing number of new and established democracies are experiencing a loss of democratic quality. While many democratic political systems suffer from gradual erosion, some have already reached the point where “stealth authoritarianism” slides back into open autocracy. According to the Bertelsmann Transformation Index, examples can be found in most regions of the world, and even in the European Union, where Hungary’s Victor Orban used the pandemic as an excuse to establish Europe’s first Corona dictatorship. As political leaders seize powers to fight the virus, worries grow if they will give up accrued powers once the crisis eventually subsides.

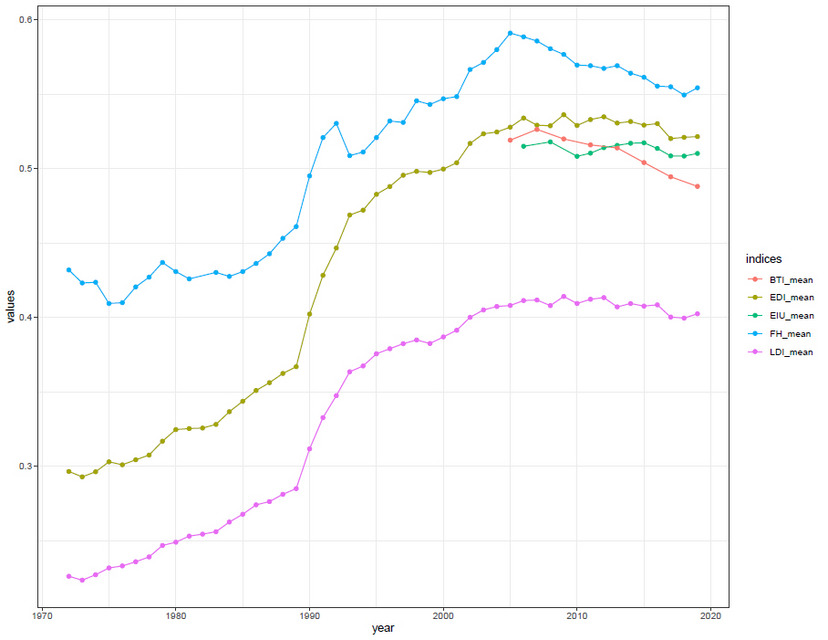

Figure 1: Global Democracy Levels, 1973-2019

Note: Democracy scores are standardized from 0 to 1; higher scores indicate a higher level of democracy. Data from Freedom House Index , the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index (EIU), the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Source: Aurel Croissant

Whether democracies in the Asia-Pacific region will regress or fail is of crucial importance for democracy’s global competition with authoritarianism in the twenty-first century. The region is both the most economically powerful and the most populous region in the world. It is home to two of the three largest democracies in the world, India and Indonesia. At the same time, almost all recent examples of successful authoritarian modernization can be found in Asia. In contrast to highly predatory autocracies in the Middle East, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, non-democracies in Asia-Pacific often achieve economically sound governance and high collective goods provision. Since the early 2000s, the People's Republic of China has become an authoritarian global player with unique “sharp power”, and analysts highlight China’s role as a global provider of innovative methods of autocratic control and repression. It comes therefore as no surprise that scholars discuss the possibility of a new Asian – essentially Chinese – alternative to both liberal capitalism and democracy.

"Whether democracies in Asia will regress or fail is of crucial importance for democracy’s global competition with authoritarianism in the twenty-first century."

Democratic Regression in Asia?

The Asia-Pacific region sends contradictory messages in the debate about a global decline of liberal democracy. Democracy has long been an exception in the region. A recent study conducted by the Bertelsmann Stiftung notes that Asia’s rushed socio-economic development since the 1960s resulted in a “compressed modernity” that has “strained the social fabric of the societies” and “neglected the democratic process”. Yet, the region has also seen its share of transitions from authoritarian rule to democratic governance in recent decades. Although consolidated democracy is the exception, the Asia-Pacific region is much more democratic today than 30 years ago.

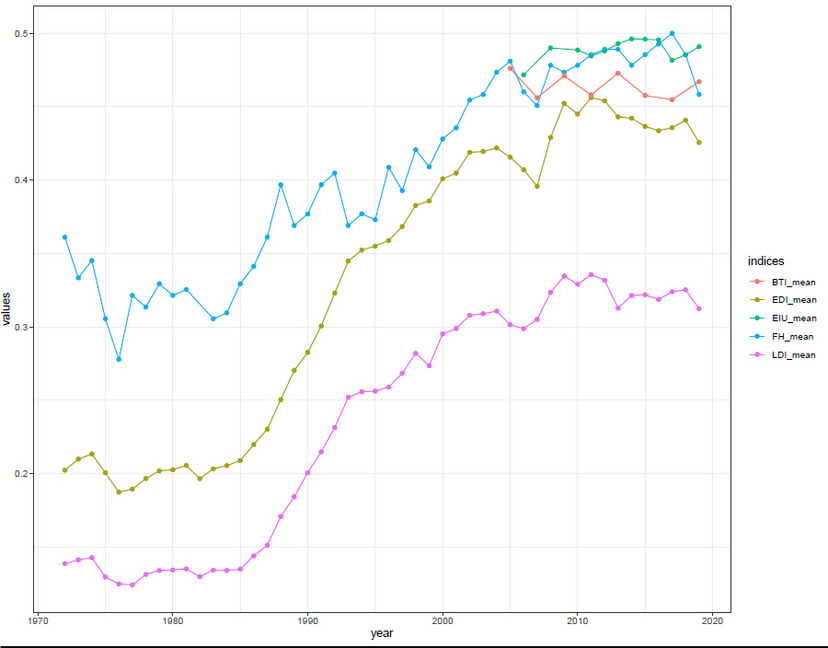

Figure 2: Asia’s Democracy Level, 1973-2019

Note: Country sample includes Taiwan, South Korea, Timor-Leste, Mongolia, India, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Philippines, Singapore, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Vietnam, China, Myanmar, Thailand, Afghanistan, Cambodia, Laos, and North Korea. Source: Aurel Croissant

At the same time, there is considerable diversity in the levels of democracy in the region and the data in Figure 2 suggest that, with few exceptions, Asia has joined the global wave of democratic regression. There are only three liberal democracies in the region – Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. While Taiwan is often celebrated as a resounding success story of the third wave of democratization, South Korea has just recently emerged from an extended period of democratic backsliding under conservative administrations between 2008 and 2016. Democratizations in Timor Leste and Mongolia have been relatively successful, given the circumstances, though recent constitutional crises suggest that democracy in the two countries is still unstable and prone to corruption and serious conflicts between political institutions. Other Asian nations have experienced substantial democratic erosion since the 2000s. Examples also include older democracies such as Sri Lanka and—most alarmingly, given its importance as the world’s largest democracy—India. Democratic quality is also in decline in the Philippines, whose polity has perhaps already crossed the line into autocratic territory, and, though less severe, in Indonesia. In places such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Thailand, the crisis of democracy culminated in coup d’états and military putsches. While the current democratic recession affects many democracies, authoritarianism in Hong Kong and Cambodia is also hardening, and countries such as Myanmar and Malaysia, which recently had embarked on processes of political liberalization, see reform governments faltering and democratic reforms failing. Finally, hard-line autocracies in Vietnam, China and North Korea show no intention to lessen their control over state and society.

Modes and Outcomes of Democratic Regression

A current overview of democratic regressions in the Asia-Pacific region by the author identifies fourteen episodes in nine countries since the turn of the century. In about half of these episodes, democratic forces managed to contain the process of backsliding before democracy broke down. Among these “near misses”, South Korea, Indonesia and the Philippines temporarily recovered at the level of democratic quality similar to that in the year before democratic erosion started. Yet, after recovering for a few years, Indonesia and the Philippines entered a new phase of democratic decline under new governments led by Presidents Duterte and Joko Widodo (alias Jokowi). Here and in India, democracy continues to regress. One certainly hopes that this authoritarian turn will not do permanent damage to electoral democracy, though a more definite answer is for posterity to uncover. In the seven cases, which fell below a minimum threshold of electoral democracy, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Thailand saw a “quick comeback” within five or less years, though democratic revivals in the last two countries were short-lived. Another important finding is that countries like Nepal, the Philippines, Thailand and Bangladesh went through more than one democratic recession. Such a vicious cycle of regression, revival and renewed regression suggests that once a democracy enters a period of decline, the chance increases that it will remain vulnerable to further degradation. This may also be the case in Sri Lanka, now that the authoritarian Rajapaksa clan is back in power.

Democratic regressions take various forms and proceed in different modes. As elsewhere, not armed revolutionaries, military adventurers or foreign aggressors are leading the current wave of autocratization in Asia. Rather, executive aggrandizement, i.e. nominally democratic incumbents using political power to reward political friends while punishing critics, to curtail independent news media, civil and political liberties, and to degrade constitutional checks on executive power and the rule of law, constitutes the modal form of contemporary democratic regressions in the region.

This is a remarkable change compared to the pre-2000 period, when executive and military-led coup d’état was the weapon of choice for autocratizers. As the examples of Modi in India and Duterte in the Philippines demonstrate, each step taken might conform to the letter of the law. Its effect is not visible immediately and, hence, it might be difficult to identify ex post a tipping point when democracy died and was replaced by elective dictatorship.

This said, illegal attempts to remove a democratically elected executive from office are not a thing of the past but have changed their rationale. “Promissory coups”, that is, the illegal seizure of a government by a group of military and civilian elites, who claim to defend democracy and promise to hold elections in order to restore democracy, took place in Pakistan (1999), the Philippines (2001), Bangladesh (2006), and, twice, in Thailand (2006, 2014).

While analytically useful, such typologies of democratic backsliding are sometimes empirically problematic. This is evident in a case such as Indonesia (2007-2013), which does not easily fit any particular backsliding mode. In Bangladesh under the rule of Prime Minister Hasina Wajed (since 2009), in South Korea under Presidents Lee and Park (2007 to 2016) and in Sri Lanka until 2015, elements of executive aggrandizement and strategic election manipulation—manipulating the rules of electoral competition in order to make incumbency permanent—merged into a wider syndrome of democratic regression. Sometimes, the political dynamics of different varieties of backsliding are causally connected. The case of Thailand illustrates this well. From 2001 to 2006, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra managed to weaken checks on executive power one by one, marginalizing opposition forces, who lacked the power to challenge Thaksin’s preferences, and effectively controlling most democracy-watchdog organizations. Following nonviolent mass protests against the incumbent government and royal intervention to block manipulation of the electoral process by the government, a military coup d’état deposed Thaksin in September 2006. The downfall of the Zia government in Bangladesh in December 2006 exhibits similar traits. The generals who spearheaded promissory coups against Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif (1999) and a pro-Thaksin government in Thailand (in 2014) also justified it as a correction of the democratic process, though the main goal was to protect the political status quo against intra-elite conflicts and deepening tensions between new and vested social interests.

Drivers of Democratic Regression

Generally, democracy is weakened by internal and external factors. Obviously, the decay of democracy seems to occur and tends to be more severe in poorer, less developed countries and lower quality democracies, though these factors cannot plausibly explain a case like South Korea, with a more advanced economy, a more vibrant civil society and stronger democratic institutions than most other Asian nations.

Furthermore, the assault on institutions of horizontal accountability, political rights and civil liberties is internally related to social polarization and the mobilization of diverse cultural and political identities, which feed on local consequences of global trends such as technological change and globalization, and rising levels of economic inequality. Praetorian legacies, ‘horizontal inequalities’ between ethnic, sectarian or regional groups that coincide with identity-based cleavages and low levels of social cohesion also weaken democratic resilience in many places. The generally low support for liberal democratic values in most Asian democracies and a serious deficit of popular trust in fundamental institutions that underpin a democratic system also raise questions about the sustainability of democratic change. Last, political agency matters, too. A deinstitutionalizing role of political leaders, strategic opportunism and the failure of elected officials and political institutions to keep pace with growing demands contribute to the rise of authoritarian populist movements and illiberal leaders in countries such as the Philippines, Pakistan, India, and Indonesia. Populists in power, then, are far more likely to damage democracy compared to more mainstream politicians.

"Although not a direct “cause” of democratic decline, the apparently growing influence of China’s governing model is increasingly affecting the domestic politics of both democratic and authoritarian countries throughout the region.”

Externally, China has become a major source of ideational and material support for autocracies such as Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand, as well as illiberal leaders in Sri Lanka and the Philippines. Even in Indonesia, one of the softer cases of democracy decline, government officials openly praise China’s authoritarian governance model. Speaking at a meeting of provincial governments in Jakarta in November 2019, the Indonesian Minister of Home Affairs, Tito Karnavian, contrasted the economic success of China and other authoritarian countries such as Vietnam with the economic stagnation allegedly experienced by democratic countries. He wondered aloud: “In China, they have only one party. It’s a non-democracy, and the economy is leaping ahead.” Although not a direct “cause” of democratic decline, the apparently growing influence of China’s governing model is increasingly affecting the domestic politics of both democratic and authoritarian countries throughout the region. Pro-democratic forces in Taiwan and Hong Kong are facing aggressive attempts by China and its agencies to promote the virtues of nondemocratic government. Much scholarly attention has also focused on China’s growing investments and economic presence in the Asia-Pacific, including through such efforts as the Belt and Road initiative.

China’s influence rising, and her role as a regional power that provides alternative sources of economic, military and diplomatic support for autocratic or authoritarian-minded government, clearly limits western leverage and contrasts with the loss of U.S. leadership in democracy promotion. Undeniably, there has been a significant (though not irreversible) weakening of American soft power as a democratic role model under the Trump administration. At the same time, neither the European Union in Brussels nor democratic governments from within the region, such as the Abe government in Tokyo or the Modi administration in New Delhi, have attempted to assume Washington’s role and close the void. While western democracy assistance in the 1990s and early 2000s contributed to the survival of democracy in unlikely places, the loss of credibility of democracy promotion as a goal of foreign policy on both sides of the North Atlantic might have unintended but palpable consequences, especially in situations of democratic backsliding, when external support would be needed most.

Sources of Democratic Resilience

Yet, the Asia-Pacific region also offers some important insights into the factors and mechanisms that contained autocratization or enabled cases of autocratic reversal to return to democracy. Scholars discuss three accountability mechanisms as potential remedies of democratic regression. Institutions of “horizontal accountability” refer to the ways in which different centers of authority such as legislatures, the judiciary, inspector generals and internal auditors constrain the executive or one another’s actions. Mechanisms of “vertical accountability” refers to the way in which ordinary citizens, collectively constituted as the electorate, can impose constraints on the rulers when regular elections give the power to remove them from office. Finally, mechanisms of “diagonal accountability” are similar to vertical in that it connects citizens to rulers, though exercised informally via direct action.

In the Asia-Pacific region, mechanisms of “horizontal accountability” seem to be least effective. Often, these institutions lack institutional capacities and political autonomy, and they are the first to be attacked as bastions of undemocratic elitism and agents of the “deep state”. The striking lesson of the successful cases of democratic regression in Asia is that governments need not take unconstitutional steps to secure domination over supposedly independent watchdog institutions. Contrary to what democracy crafters and institution-builders had hoped for when writing constitutions and organic laws, these institutions are mostly unable to rescue democracy but are the first to fall.

"Elections alone are not an effective tool to stop autocratizers. In fact, they later often enjoy considerable popular support."

Mechanisms of “vertical accountability”, especially transparent and clean elections, offer options of democratic resistance that seem more promising, especially if defection of elites from within the political camp aligned with a potential authoritarian weakens the incumbent around election time, and opposition parties manage to mobilize voters who are determined to punish a government that committed transgressions against democracy. However, most countries, in Asia and elsewhere, do not take this road. Elections alone are not an effective tool to stop autocratizers. In fact, they later often enjoy considerable popular support. When voters react to what they realized to be a threat to their democratic freedoms, they may already have lost the ability to remove the incumbent by democratic means. To our best knowledge, there are only two cases in Asia since 1950, in which an aggrandizing government lost an election: one is India in 1977, and the other is Sri Lanka in 2015, and both outcomes resulted from massive elite defections from the ruling coalition.

The weakness of institutions of checks and balances and the ability of wannabe autocrats to create an “uneven playing field” in elections by using legislative majorities and administrative powers leaves mechanisms of “diagonal accountability” as the most, and perhaps only, effective counter-balancing mechanism. Examples for the political power of ordinary citizens such as the Wild Strawberry and Sunflower Movements in Taiwan, the Candlelight Protests in South Korea or the current wave of nonviolent mass protests in Hong Kong suggest that civic resistance mobilized by civil society and opposition parties is the “last line of defense” against democratic regression. Advocacy and civil rights groups, other social organizations, students as well as concerned citizens in some South and Southeast Asian nations have also attempted to act as bulwark against the rise of authoritarianism but so far have often gained less traction and achieved weaker impact. Moreover, in light of shared concern about Chinese influence, pro-democracy actors in Hong Kong and Taiwan have begun to cooperate.

Of course, reliance on mechanisms of civic resistance involves short-term and long-term political risks. In the short-term, wannabe-autocrats may react with counter-mobilization, contributing to further polarization and conflict escalation. This may trigger a chain of mobilizing events culminating, in the worst case, in political violence. In the long-term, nonviolent mass mobilization may leave a difficult legacy of street politics. Once politics has left the institutional arenas, it might be difficult to channel it back into the institutions after autocratizers have been removed from office.

Nonetheless, a glance at the examples of resilient democracies in Asia suggests that an active civil society and institutionalized political parties represent potential safeguards against the rolling back of democratic rules and the distortion of free and fair election results by incumbents. The capability of democratic oppositions and organized citizens to threaten sanctions against anti-system behavior make democratic institutions more resilient. A strong, mobilized civil society and party institutionalization, which come with reliable bases of support and robust organizations, dis-incentivize potential autocrats to degrade democracy and enable democratic activists and party leaders to respond effectively if they nonetheless start an attempt.

On the other hand, the Asian experiences also offer some worrisome lessons. One is that for “diagonal accountability” to be a mechanism of democratic resilience and resistance, a sufficient number of citizens must still prefer a democratic form of government and have some degree of trust in democratic institutions. However, in many Asian societies, popular support for democracy and trust in democracies’ core institutions is weak and has been eroding somewhat in recent years. Moreover, illiberal and autocratic incumbents may also mobilize their supporters in counter-demonstrations that intimidate opposition, as for example in Thailand, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India.

Outlook - Reversal or Revival of Democratization in Asia?

Clearly, the dynamics of democratic regression and resilience in Asia need a much fuller treatment than the space available here. In all likelihood, this is a subject that will continue to demand close scrutiny for some time to come. In particular, more rigorous analysis is needed to understand their geopolitical implications and how specific events that erode democracy are shaping regional and global politics. In fact, as democracies in Asia backslide and authoritarian systems are hardening again, some observers see the political dynamics unfolding in parts of the Asia-Pacific region as reflecting the beginning of a new global competition between Western notions of liberal democracy and capitalism on the one hand, and a Chinese model of state-capitalist authoritarianism that Beijing is now turning outward. For some, democracies in Asia and elsewhere will be engaged in a life-and-death struggle with globalized authoritarianism.

It is important, however, to emphasize that Chinese policies are not the “cause” of democratic regression in Asia. The causes for democratic regressions are primarily internal and they have more to do with structural and political weaknesses, the strategic behavior of political elites and the local consequences of global developments, than with the behavior of autocratic states such as China. Even though the Chinese government may not actively support anti-democratic actors in their attempt to abolish democracy and does not have a deliberate policy of promoting its own model of authoritarian governance abroad, it is hard to ignore that China seeks to promote its own preferred ideas, norms, and approaches to governance. The aforementioned anecdote from Indonesia is but one of numerous examples of a much wider phenomenon: the apparently growing influence of China and its governing model throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Beijing’s role as a new global power that provides alternative sources of economic, military and diplomatic support for governments in Asia and elsewhere clearly decreases the cost of authoritarian abuse and mitigates the potential impact of punitive action by democratic governments in the West.

"Even though they do not have a monopoly on ignorance and dysfunctional governance, the global health crisis has made very clear, that having a populist government is perhaps the worst of all worlds."

Undoubtedly, the difficulties of democratic governments and institutions to cope with old and new challenges contrasts with the ability of authoritarian governments in China, but also in Singapore and Vietnam, to provide political stability, fight poverty and provide access to improved government services for broad segments of their societies. These developments contribute to the revival of the ancient debate about the virtues and perils of democratic versus authoritarian governance models. Due to the lack of space, this policy brief cannot dive deeper into this debate. However, one cannot but point to the most recent developments in the region and worldwide, which are related to the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic. As with economic development, prima facie no systematic differences in the success between democratic and autocratic systems can be identified in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic: Singapore and Hong Kong (authoritarian) reacted efficiently, Taiwan and South Korea (democratic) as well. Many governments, democracies and autocracies alike, in Asia and elsewhere have been awfully unprepared and slow to react. But a quick glance at how authorities in China initially suppressed information about the the outbreak of the virus and how Beijing is sizing on the pandemic to attack Hong Kong’s democracy movement; at India’s uniquely mishandled rollout of a 21-days lockdown of the whole county or Duterte’s ineffective strongman tactics will suffice. Even though they do not have a monopoly on ignorance and dysfunctional governance, the global health crisis has made very clear that having a populist government is perhaps the worst of all worlds: Aversion to “expertise” and rejection of “establishment” authorities is a central element in the politics of populism. Just as journalists and their families are intimidated, judges are demonized and people from minority groups are singled out for their alleged disloyalty, researchers are subjected to loyalty tests, and there is little appreciation for academic expertise.

"Within the Asia-Pacific region, the examples of democratic Taiwan and South Korea prove that the free flow of information and an active civil society are the best treatment for the coronavirus outbreak.”

One should compare this to the apt and timely reactions of liberal democratic governments in South Korea and Taiwan. The Coronavirus outbreak shows that both democracies and autocracies can demonstrate a surprisingly poor ability to learn, prepare and act in a coherent and timely manner. Yet, within the Asia-Pacific region, the examples of democratic Taiwan and South Korea prove that the free flow of information and an active civil society are the best treatment for the Coronavirus outbreak. Among Asian countries, those governments performed better, which allowed for more information, more civil society engagement in crisis response, and are more accountable to public scrutiny and mechanisms of vertical and, especially, diagonal accountability.

In light of a shared concern about the revival of authoritarian challenges in the region and the loss of U.S. leadership in advancing democracy abroad, pro-democracy actors in a number of Asian countries had already begun to cooperate before the pandemic struck the region. Fresh forms of cooperation are beginning to take shape among Asian democracies in the civil society sector, and multiple platforms created by civic organizations in South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, India and Indonesia aim to bringing together pro-democratic actors from across the region. With a self-centered U.S. government and an assertive China, German and European governments and civil societies should step in and support such efforts. Moreover, with backsliding democracies in the European Union, democracy activists and pro-democratic political actors in the West may even learn a lesson or two from their like-minded peers in Asia.

Background

This policy brief builds on discussions at the workshop “Democratic Backsliding in Asia”, hosted by Heidelberg University and sponsored by the Bertelsmann Stiftung in December 2019, and previews arguments in a forthcoming special issue of the journal Democratization on the same topic.

News

We would like to keep you informed about our activities. Please register here to receive our publications as well as invitations to our events: http://b-sti.org/DeutschlandundAsien