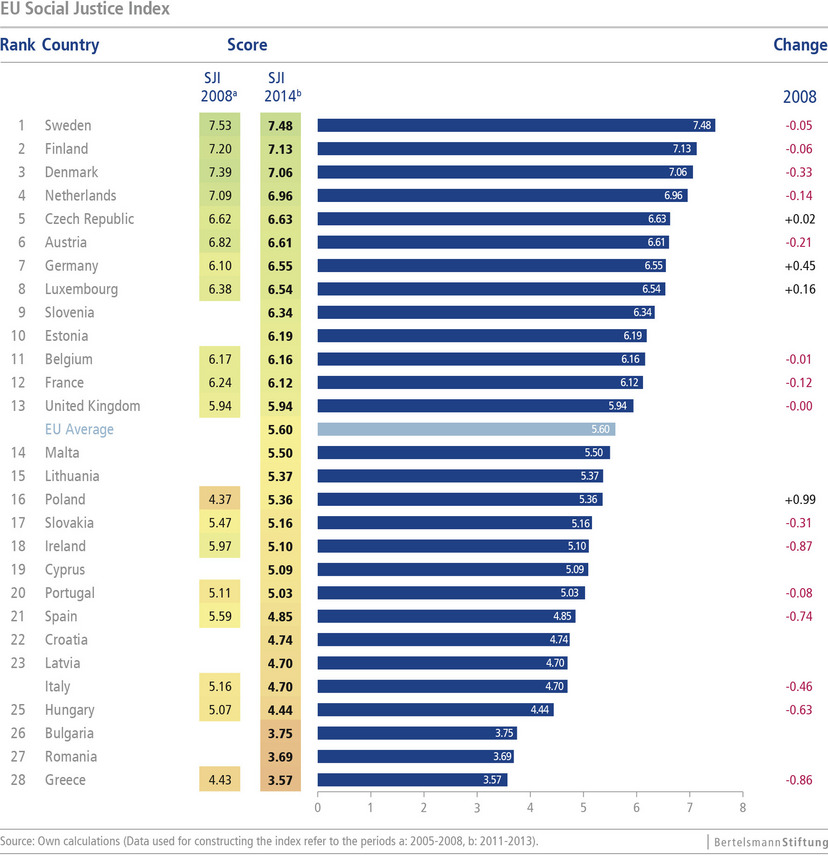

The social imbalance between the affluent northern European states and the many southern and south-eastern European countries has considerably intensified over the course of the crisis. Whilst there still is a high level of social inclusion in Sweden, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands, social injustice in countries such as Greece, Spain, Italy or Hungary has increased. In the crisis-ridden states of the EU in particular, it has not been possible to administer the massive cuts in a balanced manner. This is the result of a new index comparing the justice of all 28 EU states, which was published today by the German foundation Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Alongside the North-South divide, the analysis is particularly critical of the growing imbalance between generations. According to the analysis, young people are much harder hit by social injustice than those who are older. 28 per cent of children and young people are threatened by poverty or social exclusion right across the EU, which is significantly more than in 2009. In contrast, poverty among the elderly has declined in several cases. "The growing social divide between member states and between the generations can lead to tensions and a considerable loss of trust. Should the social imbalance last for long or increase even more, the future of the European integration project will be threatened," says Dr. Jörg Dräger, member of the foundation's Executive Board.

The top rankings of the Nordic countries and the Netherlands are mainly due to good policy outcomes in the fields of poverty reduction, labour market access and social cohesion and non-discrimination. Although the Nordic countries noticeably feel the effects of the crisis, the degree of social inclusion in these countries is still high. Finland and the Netherlands were recently able to reduce child poverty contrary to the EU-wide trend. In the top ranking countries, the challenge for the future is especially to overcome the continuing poor access opportunities of immigrants to the labour market, as well as fighting the relatively high youth unemployment in Sweden (23.5%) and Finland (19.9%).