By Christof Schiller and Leon Klein

Corruption is once again a hot-button issue, and not just because of the cash-for-influence scandal involving the European Parliament’s former vice president, Eva Kaili, who is currently sitting in prison. Today’s release of Transparency International’s 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) also paints a gloomy picture of corruption and graft around the world. The CPI, which has been assessing perceived corruption in 180 countries since 1995, draws on several sources, including the data provided by the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI).

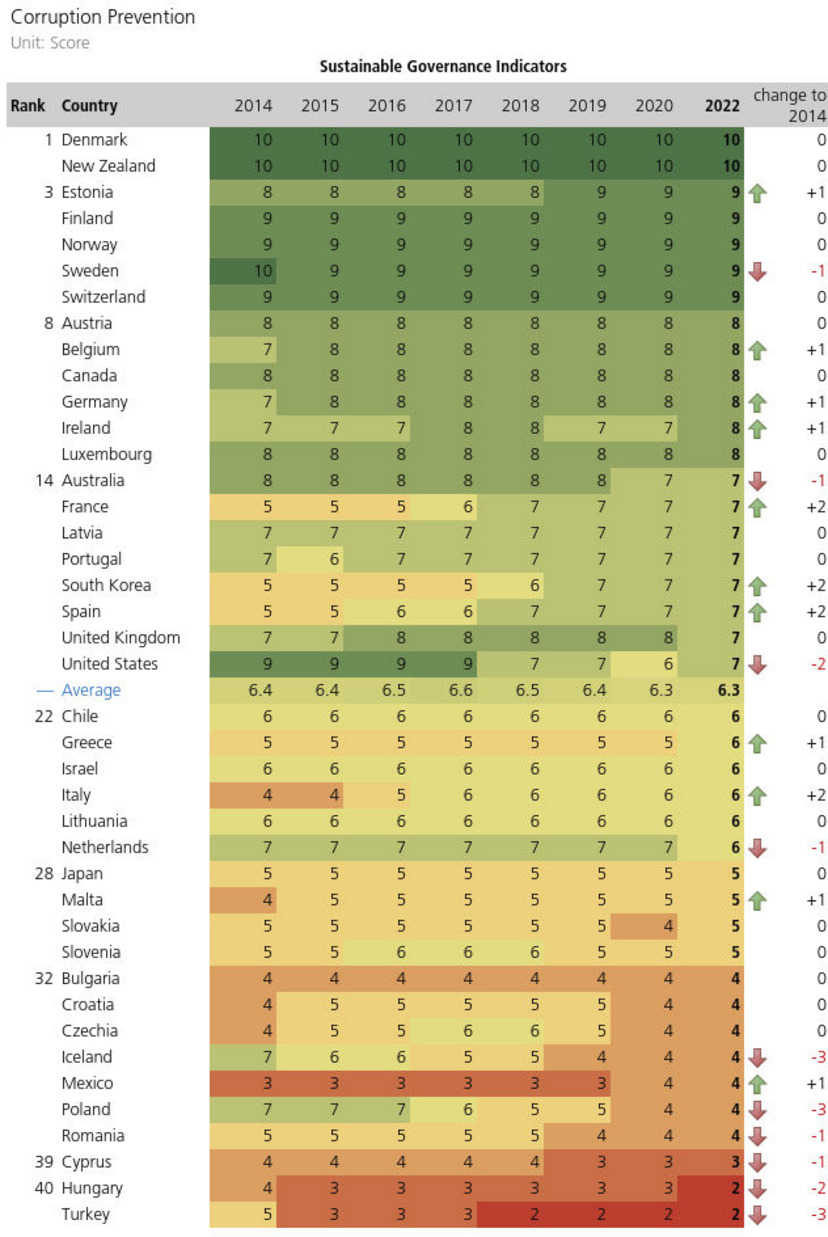

Since 2009, the SGI project has been examining the resilience of OECD and EU countries in terms of the robustness of their democratic processes and institutions, the quality of governance and the sustainability of their policies targeting economic, social and environmental issues. Overall, SGI findings show a strong and stable correlation between success with preventing corruption on the one hand and good governance as well as the formulation of effective and sustainable policies on the other. In short, countries that effectively curb the abuse of office are also better at implementing more sustainable policies.