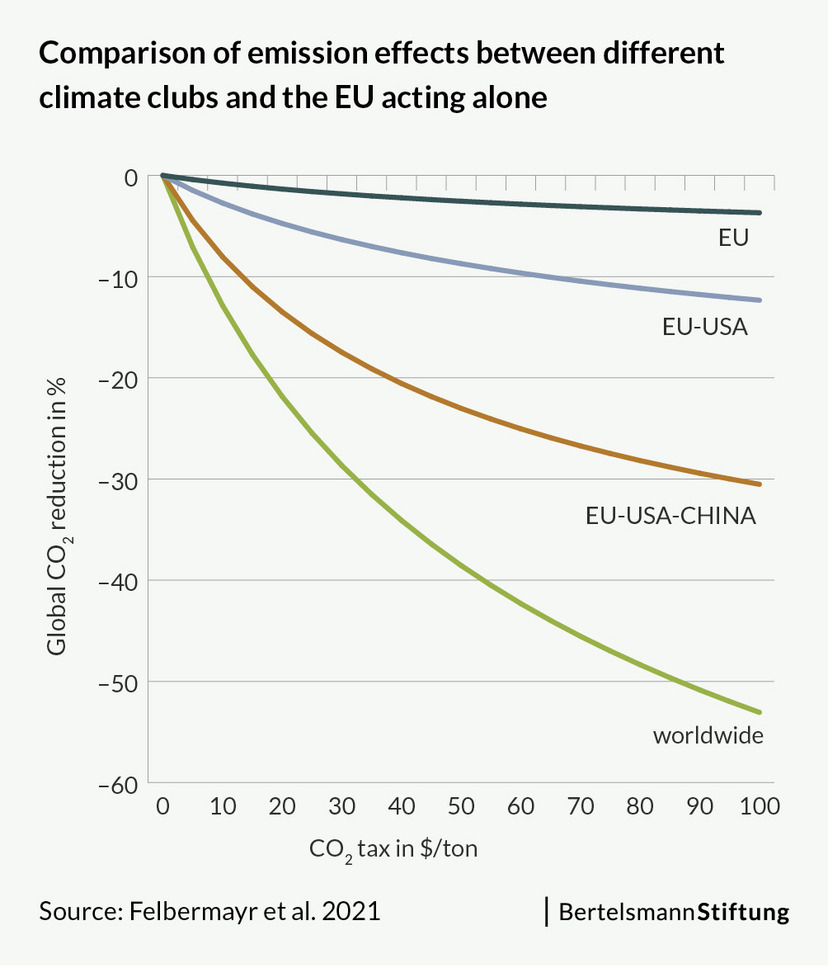

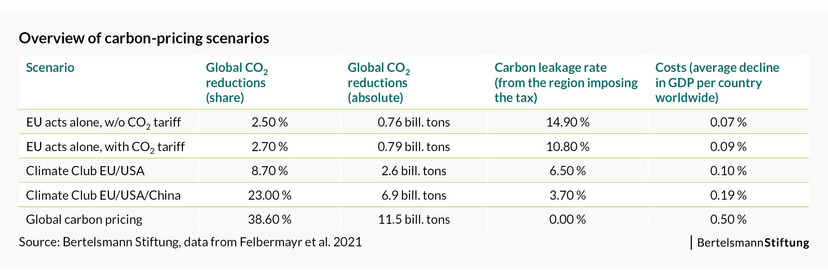

The first finding: “By unilaterally raising the price of carbon, the EU can contribute very little to climate protection efforts, since global emissions would only fall by 2.5 percent,” says Thomas Rauch, economic expert at the Bertelsmann Stiftung. “But if many countries joined together in a global climate club, a $50 increase in the carbon price would cause greenhouse gas emissions to fall by almost 40 percent – and the economic costs would be moderate.” If the resulting tax revenues were redistributed on a per capita basis, every country would experience a long-term decline in its gross domestic product of just 0.5 percent on average. And if only the three largest emitters – the US, EU and China – were to join forces, emissions would still fall by 23 percent.

Since global or transregional cooperation of this sort is currently unlikely, the risk exists that, whatever form they take, regional responses like the EU’s unilateral effort would lead carbon-intensive sectors – the steel and cement industries, for example – to relocate their production to other regions in which CO2 emissions are not taxed at all or only slightly. This phenomenon is known as carbon leakage. To counteract this problem, the EU plans to present a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) this July that would compensate for the difference between the price of carbon in the EU and the price in the countries it trades with that have less stringent climate policies. All goods sold in the EU would thus reflect the EU emissions price – regardless of whether the product in question originates in the EU or somewhere else. While the CBAM would prevent carbon leakage and increase the competitiveness of Europe’s carbon-intensive industries, it would have little impact on global emissions, since the production that would have migrated abroad without the mechanism would take place in the EU once again. Instead of a 2.5 percent decline in global emissions, the EU’s border adjustments would achieve a reduction of 2.7 percent.