Mini-publics, citizens' assemblies and citizens' panels with randomly selected citizens are spreading across Europe. Better political decisions, more trust in democratic processes - politicians increasingly take note of the advantages of new forms of deliberative participation and establish permanent mechanisms in their representative systems.

The "East Belgium” model is one of the most developed approaches in linking deliberative forms of participation with parliament and government. It has become a role model of how new forms of citizens participation can be embedded into the political system. This shortcut shows how permanent citizens' assemblies can go hand in hand with the functioning of parliamentary and governmental politics.

Download the SHORTCUT as PDF here.

‘A Belgian experiment that Artistole would have approved of’

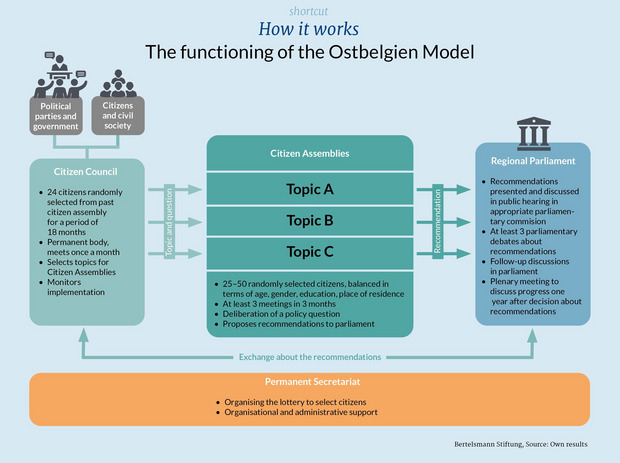

This is how The Economist labeled the citizen participation Ostbelgien Model (OBM). The OBM institutionalizes the use of deliberative democratic methods with randomly selected citizens in policymaking for the German-speaking community of Belgium (also called Ostbelgien). Although the region is very small (fewer than 80,000 inhabitants), it is a federal sub-state entity with own legislative powers like a Bundesland. The OBM combines a permanent Citizen Council that selects the topics to be deliberative and performs several coordinating tasks with one to three Citizen Assemblies every year. Both are composed of citizens drawn by lot. The Citizen Council follows up the recommendations with parliament.The model is one of the most far-reaching applications where traditional represen-tative democratic institutions are connected to deliberative assemblies of randomly selected citizens:

- The deliberative assemblies’ agenda is completely left in the hands of a citizen body. Politicians have no control over the topics that will be discussed.

- The follow-up of recommendations is a formal task of a citizen body. In most other deliberative processes, there is no organised citizen control of the political follow-up.

- A law institutes this model, making it the first region worldwide with legislative power where a permanent council of citizens and annual citizen assemblies are mandated by law.

What happened so far?

Three Citizens’ Assemblies have been initiated by the Citizen Council until now on the topics of improving conditions in health care, inclusive education and affordable housing. The cycle of the first Assembly is described here to illustrate how the model works in practice.

The first Citizen Council meeting took place in September 2019, half a year after the bill installing the OBM was approved in the regional parliament in February. Close to thirty proposals were submitted by citizens after the first call for topics. The Citizen Council decided that the question handed over to the first Citizen Assembly would be “Care is important for all of us. How can we improve the conditions in health care for staff and patients?”.

This first Citizen Assembly took six months in 2020, which was longer than anticipated due to the corona pandemic. The citizens worked on four different aspects of care work. They proposed 14 recommendations to parliament at the end of their work.

The recommendations, for example, covered ways to stimulate more young people to choose healthcare as an educational track and to use new IT solutions to reduce the large administrative burden for care workers. Another recommendation was related to using internal and external evaluations to improve quality management in care homes.

The presentation of the recommendations in parliament took place early October 2020. By mid-December an “Opinion” from the parliament and government on the recommendations was presented and debated. This 30-page document will be the guideline for the follow-up. The Citizen Council—in its monthly meetings—connects with the parliament to see how the implementation is progressing.

When citizens oversee the agenda-setting and follow-up, their involvement in a single completed process can take close to two years from start to finish. As several of these processes already run simultaneously, the Citizen Council acts as the coordinating body to monitor all these different steps. In one meeting, the Council might be looking at how much time will be needed for an upcoming assembly, but also plan a commission meeting for the follow-up of another Assembly that ended a few months before.

Success

- Unanimous support by all parties in the regional parliament, giving it a high level of legitimacy.

- A lot of media attention from major news outlets throughout Europe, such as the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Der Spiegel, NRC Handelsblad, The Economist, and El Pais.

- The Citizen Council receives many topic proposals. The process is seen as a meaningful way to achieve citizen-centered policymaking.

- Many citizens want to participate. Over 9% of those who are invited are willing to take part. Compared to other Citizen Assemblies, that is a very high number.

Challenges

- The need for strong administrative capacities and resources. This includes checking whether topics match regional competences and drafting responses to every recommendation.

- Getting local media attention to the process. Research in April 2020 showed that only half of the population of the region even knew the OBM existed. Regional media only sparsely report on the process.

- Connect this process to traditional civil society actors. As they play an important role in many policy fields, a stronger link would increase the legitimacy of the process.

- Keep high participation rates. The OBM requires enough citizens to be part of Assemblies to function, which can be difficult for certain profiles of citizens if the response rates were to decline.

Paving the way for innovation and institu-tionalisation of deliberative democracy

Ostbelgien is clearly seen as a trailblazer in innovative citizen participation in Europe. The Ostbelgien model has received a lot of international media attention and has also become a household name for anyone interested in deliberative methods. This is down to several factors.

First, the small size of the region has always allowed for close connections between representatives, citizens, and civil society. Most MPs continue to have regular day jobs.

Second, there was a broad willingness to experiment with citizen participation throughout the last decade. One of these experiments was a citizen assembly on childcare in 2017. This Assembly was seen as a success by most politicians involved and therefore paved the way to use this method in a more structural way.

Finally, in 2018, the region had two politicians at the head of its legislative and executive that spearheaded a bold experiment in institutionalising deliberative democracy. The OBM also emphasizes how the institutionalisation of deliberative methods makes them a tool of political socialisation. Members of Assemblies learn up close how policies are made and what role institutions have. Research shows that, in general, participants in these processes have higher support for political institutions and democracy after participating because they understand them better. Research equally demonstrates that, subsequently these participants often become engaged in civil society and sometimes even party politics.

Ultimately, the OBM serves as a great tool for policy-learning for other polities who want to institutionalise deliberative methods. The debate centred around this topic was purely theoretical until the OBM was put in place. Now there is a place to observe what works and what still requires improvement. Today, we see more and more initiatives that are following suit.In Paris, for example, the city council voted a bill in October 2021 that installed a similar process in the city. In addition to its Ostbelgien design, the Paris model can also be used to evaluate past policies and set the topic of the participatory budget program of a city every year.

Ostbelgien is not the only example in Belgium

About a year after the OBM started in Eupen, the Brussels regional parliament decided to institutionalise deliberative methods for its policy-making work. The parliament opted for a different model, with its most visible design feature being that MPs and citizens work together in mixed deliberative committees. The committees are composed of 15 MPs and 45 citizens, and after having been informed about a topic and been deliberated on, they propose recommendations to the parliament. One of the strengths of this specific model is that, when politicians are part of drafting recommendations, it increases the likelihood of political follow-up as there is political co-ownership. This Brussels model has no fixed citizen council, and the agenda-setting and follow-up are done by the parliament itself.

New developments

While examples of institutionalisation of deliberative democracy are still sparse, it is increasingly seen as the way forward for democratic innovation. In Germany, the new governing coalition has promised to regularly hold Citizen Assemblies. In the EU, the four Citizen Panels in the context of the Conference on the Future of Europe are the most comprehensive citizen assemblies ever held at an international level. One of the recommendations of the panels is the institutionalisation of citizen assemblies in the EU.

Message to go:

Ostbelgien is the first region worldwide with a permanent Council of Citizens and annual Citizen Assemblies mandated by law.

Authors

Yves Dejaeghere

yves.dejaeghere@fide.eu

Anna Renkamp

anna.renkamp@bertelsmann-stiftung.de

Dr Dominik Hierlemann

dominik.hierlemann@bertelsmann-stiftung.de

Democracy and Participation in Europe (bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en)

Sources and further reading

Sources and further reading

The parliament of the German-speaking community runs a very comprehensive website on all aspects of the OBM at www.buergerdialog.be

The OECD has discerned eight different types of models in a recent policy paper on ways deliberative democracy has been institutionalised until now. Both Ostbelgien and the Brussels mixed committees are considered a source of a typology in this document: Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy - OECD

An academic paper looking into the genesis of the OBM as the first permanent citizen assembly has been published by Hadrien Macq & Vincent Jacquet in the European Journal of Political Research.

Imprint shortcut

Future of Democracy

© March 2022 Bertelsmann Stiftung

Bertelsmann Stiftung | Carl-Bertelsmann-Straße 256 | 33311 Gütersloh

www.bertelsmann-stiftung.en

Responsible:

Dr. Dominik Hierlemann, Anna Renkamp, Dr. Robert Vehrkamp

Cover picture: © kristina rütten - stock.adobe.com

The shortcut series presents and discusses interesting approaches, methods, and projects for solving democratic challenges in a condensed and illustrative format. The Bertelsmann Stiftung‘s Future of Democracy program publishes it at irregular intervals.

Download

Download

Supported (in part) by a grant from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the OSIFE of the Open Society Foundations. Supported (in part) by a grant from King Baudouin Foundation.

(© Open Society Foundations )

(© King Baudouin Foundation)