The current reporting period from February 2017 to January 2019 saw meaningful political changes in a number of states including Angola, Cameroon, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe – although in few of these cases was here a change to the underlying character of the political system. While Cameroon, Chad, Kenya and Tanzania have moved further away from lasting political and economic transformation, Angola, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe initially appeared to be making progress towards it. However, in Ethiopia and Zimbabwe this impression did not last beyond the end of the BTI reporting period, and the new governments of both countries now stand accused of committing similar human rights abuses to their predecessors.

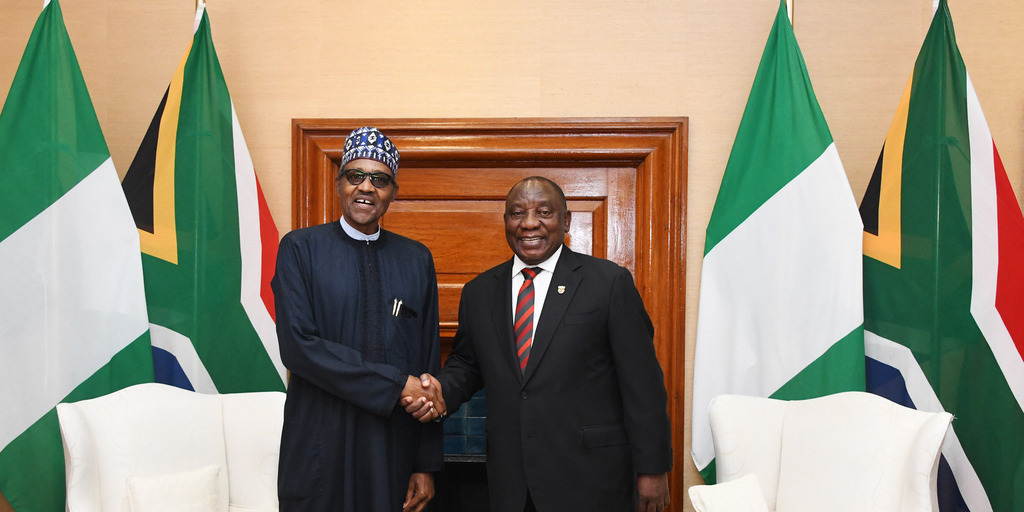

GCIS / GovernmentZA / Flickr - CC BY-ND 2.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/

A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems?

Since 2017, a number of African states have seen significant, if not transformative developments. In almost all cases, positive trends were recorded in countries where leadership change generated hope for political renewal and economic reform. However, in few of these cases there was a change to the underlying character of the political system. Political power remains highly personalized, writes Nic Cheeseman in the latest BTI Africa Report.

Leadership changes generated hope

In almost all cases, positive trends were recorded in countries where leadership change generated hope for political renewal and economic reform. This includes Angola, after President José Eduardo dos Santos stepped down in 2017, Ethiopia, following the rise to power of Prime Minister Abiy, and Zimbabwe, where the transfer of power from Robert Mugabe to Emmerson Mnangagwa was accompanied with promises that in future the ZANU-PF government would demonstrate greater respect democratic norms and values. Sierra Leone also recorded a significant improvement in performance following the victory of opposition candidate Julius Maada Bio in the presidential election of 2018, while Nigeria has continued to make modest but significant gains in economic management since Muhammadu Buhari replaced Goodluck Jonathan as President.

The significance of leadership change to all of these processes is an important reminder of the extent to which power has been personalized in many African states. It is important to note, however, that subsequent events since the end of the period under review in 2019 have cast doubt on the significance of these transitions. Most notably, continued and in some cases increasing human rights abuses in countries such as Nigeria, Tanzania and Zimbabwe suggest that we have seen “a changing of the guards” rather than a genuine transformation of political systems.

Zero tolerance for dissent

If we turn our attention to those countries that recorded negative trends, we see a very different pattern: deteriorating performance typically occurred in countries in which established leaders felt the need to adopt increasingly repressive strategies to retain control, and to subvert economic management to serve political ends as part of this effort. In some cases, this was in response to a strong challenge from the opposition (Kenya, Zambia), while in others it reflected an increase in popular unrest (Chad), and secessionist challenges to the legitimacy of the state itself (Cameroon). The only country to witness a significant decline in the absence of growing opposition was Tanzania, where the fall in the quality of governance under President John Magufuli appears to reflect more his personal leadership style and refusal to tolerate dissent than any actual increase in support for political rivals.

Regional variations

While these changes were fundamentally driven by domestic politics, the BTI Africa Report 2020 also documents important regional variations that merit further research and explanation. Southern and West Africa perform best on all three criteria – democracy, economic transformation and governance – with East and Central Africa lagging considerably behind. This reflects the historical process through which governments came to power, the kinds of states over which they govern, and the disposition and influence of regional organizations. In particular, East Africa features a number of countries ruled by former rebel armies (Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda), in which political control is underpinned by coercion and a long standing suspicion of opposition. This is also a challenge in some Central African states, but with the added complication of long running conflicts and political instability (Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo) that have undermined government performance on a number of dimensions.