Participatory budgeting has a long, worldwide tradition. Administrations and politicians regularly make financial decisions and decide on the budget for the coming years. Participatory budgeting involves the population in financial planning, and experts describe it as one of the most successful democratic innovations of recent decades–with many active participants worldwide.

International experience shows: Citizens are ready and willing to deal with tough and sometimes complicated financial issues and to make valuable proposals. Commitment, comprehensibility and trust are the keys to successful participatory budgeting–at all levels of government.

Joint expenditure planning with stakeholders – citizen participation in financial decisions

How should the state spend its money? Participatory budgeting involves citizens in this important political decision-making process. Thousands of examples from around the world show that participatory budgeting is one of the most successful democratic innovations in recent decades. The reasons for participatory budgeting vary from country to country: in Portugal, to increase trust; in Brazil—where participatory budgeting began—to prevent corruption; or in Mozambique, to reduce poverty.

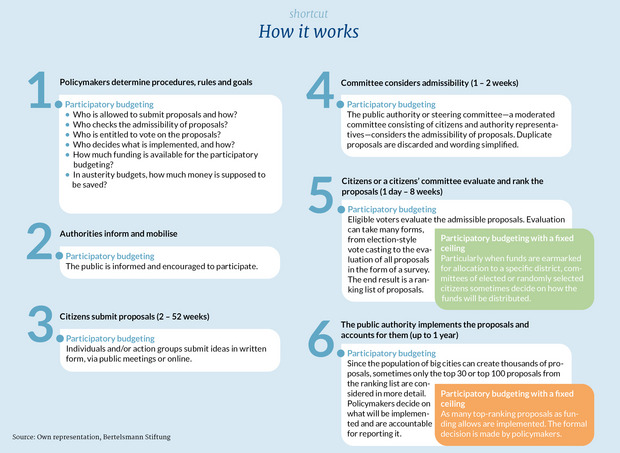

The processes follow the same basic pattern. The public authority presents a clear, transparent plan to which citizens add their proposals. The authority checks the admissibility of the proposals, which are then evaluated or voted on by citizens and policymakers. Participatory budgeting can help to create transparency and trust. It also allows public authorities and policymakers to draw up financial plans which are more in tune with the wishes of citizens, who in turn feel a stronger sense of identity with their home city, region or country.

Internationally, the final decision on participatory budgeting often lies directly with citizens. In Germany and Europe, final decisions tend to be made by policymakers and public authorities. However, even here the new variants of more binding methods of participatory budgeting with a fixed budget offer an opportunity for citizens to have the last word.

There is a long history of citizens’ involvement in the allocation of public

1869 The Swiss Canton of Zürich stages the first direct democratic financial referendum; the participation rate in referenda to date is between 22 – 83 %.

1898 Some U.S. States introduce financial referenda.

1919 Under the Weimar Constitution, the state budget may not be influenced by citizens’ initiatives.

1952 In the German Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia, local authorities must present their budget plans to the public and consider any objections – the same as for urban and rural planning.

1989 New Zealand and Brazil “invent” participatory budgeting aimed at modernising administrative processes and fighting corruption. This democratic innovation spreads northwards to thousands of other locations worldwide.

1998 First instances of participatory budgeting in Germany, in Blumberg and Mönchweiler.

2002 Berlin effectively introduces participatory budgeting with its first Urban District Fund.

2011 Stuttgart introduces participatory budgeting on a regular basis. In 2017:

9 % = 52,000 active participants, 3,457 proposals.

2014 Paris starts participatory budgeting for investments exceeding 100,000,000 € = 33 € per inhabitant, 8 % = 132,000 active participants.

2017 Ketzin (Havel) introduces participatory budgeting for sums exceeding 50,000 € = 8 € per inhabitant, 24 % = 1,594 active participants.

2017 Portugal introduces its first national participatory budgeting for sums greater than 3,000,000 € = 0.30 €/inhabitant, 1 % = 80,000 active participants, 599 projects.

2021 Small groups of artists stage the exhibition documenta 15 through collective decision on their own budget.

There are many effective ways to involve citizens in budgetary planning

Wide variety of fields

Participatory budgeting can be used for redevelopment areas, urban districts, towns, counties, regions or entire states. Some participatory budgeting schemes are limited to individual topics such as traffic and transport, while others are used as a tool to reduce debts. In school budgets, students decide on how money is spent in their schools.

- Who can make proposals?

Sometimes anyone can make proposals anonymously, in other cases only inhabitants of the city, region or country who have reached a certain age or are entitled to vote.

- What can be proposed?

In the strict sense of the term, participatory budgeting usually contains a fixed ceiling for expenditure or investments. Used in a looser sense, participatory budgeting can also involve the general public submitting ideas for the use of funds, or for potential savings or additional

income.

- Who checks the admissibility of the proposals?

As a rule, admissibility is checked by the administrative authority, an advisory committee made up of administrators and selected citizens, or a panel of citizens selected at random.

- How are the proposals evaluated?

There are various methods. Those entitled to vote frequently have as many as five votes which they can allocate to the different proposals, or each citizen can rate each proposal on a scale of two to ten—like in a survey. The end result is always a ranking list of proposals.

- How are the proposals finally selected?

Either policymakers decide which of the topranked proposals will be implemented, or as many topranking proposals are implemented as the available funding allows. In Porto Alegre or Seville, pre-defined sociopolitical aspects determine which proposals are prioritised.

Participatory budgeting is an opportunity for democracy

In global terms, participatory budget planning has a long tradition. Porto Alegre in Brazil and Christchurch in New Zealand started participatory budgeting independently of one another in 1989. Brazil was seeking democratic alternatives after the end of a military dictatorship, while New Zealand wanted to make public administration more democratic. In both cases, their efforts compelled public authorities and policymakers to create genuine, comprehensible transparency and readable financial information.

Citizens are willing and able to tackle difficult—and sometimes complex—financial issues and to take meaningful proposals. For example, in 2017, 97 per cent of participating citizens in Stuttgart stated that they would be prepared to engage in the next round of participatory budgeting. In Zürich, up to 83 per cent of the electorate have voted on concrete financial issues since 1869. In Berlin, Germany, up to 90 per cent of pupils regularly take part on participatory budgeting processes (in German: “Schülerhaushalte”) in schools.

There is a wide range of positive effects and benefits: trust and transparency are created, corruption fought, funds used more purposefully, and specific regions or sections of the population given targeted support. Experience shows that participatory budget planning is particularly successful when applied to a clearly defined region or topic. This ensures easy access to those who will benefit from the funding, maximum commitment to honouring the results of participatory processes, and maximum relevance of the topic(s) for as many citizens as possible. Key elements in ensuring the success of participatory budgeting are a clear breakdown into individual projects or topics and treating the citizens’ decisions as binding. This will ensure that as many citizens as possible participate in financial issues. Participatory budgeting helps to cement a closer relationship between politicians and citizens. This also applies to the EU.

Participatory budgeting in Stuttgart

- Every two years, citizens of Stuttgart can submit proposals for the budget of the city and its 23 urban districts from January onwards. Submissions can be made online, by letter or by phone.

- A steering committee and the local authority check the proposals for duplicates and to ascertain whether the proposals fall under the city’s municipal responsibility.

- Citizens of Stuttgart can evaluate the proposals in March, either online or in written form.

- The administrative authority checks the content of the top 120 proposals; the City Council decides which will be implemented.

- 3,457 proposals were submitted in 2017, of which citizens were invited to evaluate 2,664. 52,000 citizens returned around 3,000,000 evaluations and 12,000 comments. About half of the top 120 proposals were considered by the City Council. Among the ideas approved were, for example, artificial turf for a sports ground, a pavilion for mobile youth social work and a feasibility study for a surf wave on the River Neckar.

Participatory budgeting in Madrid

- From January to March every year, citizens can submit proposals for expenditure for Madrid or its 21 urban districts and canvass for support from the population.

- Between April and early May, the municipal administration examines the feasibility of the projects in the order of the level of support received from the citizens.

- Between May 15 and June 30, the citizens of Madrid vote on the qualified projects that interest them most.

- Once the budget has been approved in the following year, the city council starts implementing the winning projects.

- In 2017, 3,215 projects were submitted, 720 proposals were evaluated by 39,000 people, and 311 projects eventually selected for implementation. Among the approved projects were the provision of collecting tanks for used vegetable oil, the purchase of returnable cups for public festivals, and the refurbishment of the toilets in Retiro Park.

Message to go:

The key elements of successful participatory budgeting are its binding character, clarity and trust – at all state levels.

Authors

Dr. Christian Huesmann

christian.huesmann@bertelsmann-stiftung.de

Tel.: +49(5241)81-81221

Volker Vorwerk

www.buergerwissen.de

Tel.: +49(521)5222908

Democracy and Participation in Europe (bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en)

Sources and further reading

Further reading

Participatory Budgeting World Atlas

Netzwerk Bürgerhaushalt Deutschland

Participatory budgeting in German and Austrian schools (in German)

Schüler*innenHaushalt - Deine Idee. Dein Projekt. Deine Schule.

https://schuelerinnen-haushalt.de/

Links to some individual participatory budgeting sites

Stuttgart: www.buergerhaushalt-stuttgart.de

Madrid: www.decide.madrid.es

Paris: budgetparticipatif.paris.fr

Lissabon: op.lisboaparticipa.pt

New York: council.nyc.gov/pb

Seoul: yesan.seoul.go.kr/intro/index.do

Literature

Vorwerk, Volker, und Maria Gonçalves (2020). „Partizipative Budgetplanung: Bürgerhaushalt, Bürgerbudget oder Finanzreferendum?“. Kursbuch Bürgerbeteiligung. Hrsg. Jörg Sommer. Deutsche Umweltstiftung.

Wampler, Brian, McNulty, Stephanie and Michael Touchton (2021). Participatory Budgeting in Global Perspective. Oxford University Press.

Imprint shortcut

Future of Democracy

© December 2021 Bertelsmann Stiftung

Bertelsmann Stiftung | Carl-Bertelsmann-Straße 256 | 33311 Gütersloh

www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de

Responsible:

Dr. Dominik Hierlemann, Anna Renkamp, Dr. Robert Vehrkamp

Cover picture: © flydragon - stock.adobe.com

The shortcut series presents and discusses interesting approaches, methods, and projects for solving democratic challenges in a condensed and illustrative format. The Bertelsmann Stiftung‘s Future of Democracy program publishes it at irregular intervals.

Download

Download

Supported (in part) by a grant from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the OSIFE of the Open Society Foundations. Supported (in part) by a grant from King Baudouin Foundation.

(© Open Society Foundations )

(© King Baudouin Foundation)